A Map with a Message

Russian Expansion into Neighbouring Territories 200 Years Ago

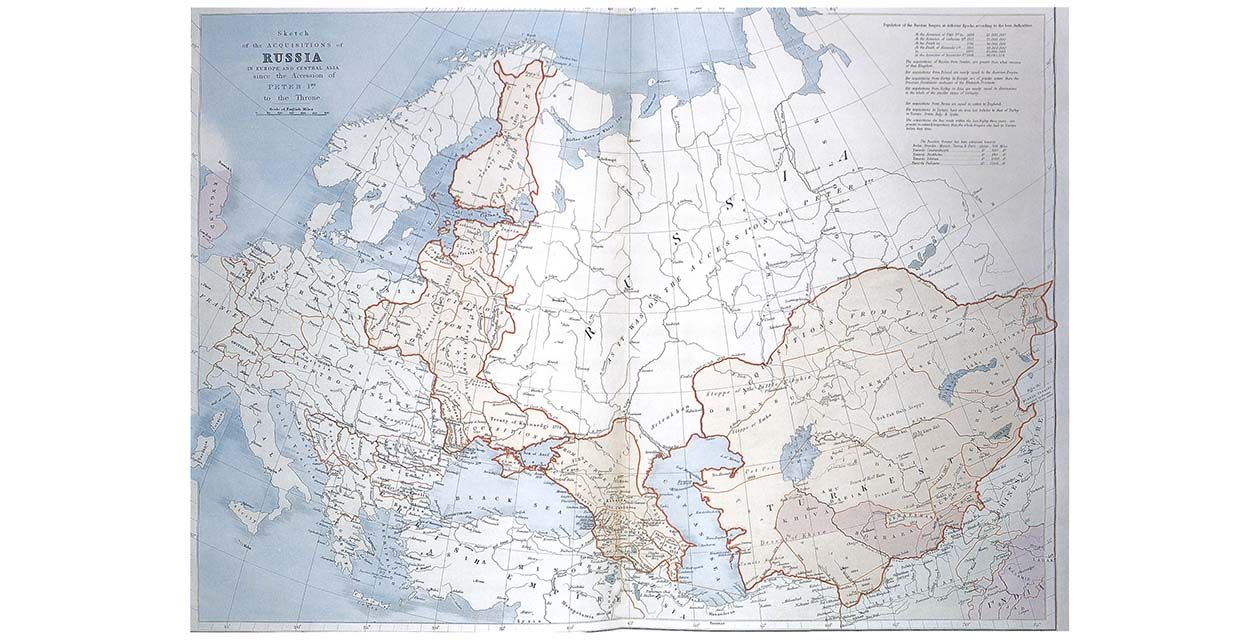

European anxieties about Russia have a long history. This map appeared in the 1887 edition of Stanford’s London Atlas, but it goes back even further, for it was originally drawn to illustrate Sir John MacNeill’s book, The Progress and Present Position of Russia, published in 1836. MacNeill’s knowledge had come from his time as British envoy to Tehran, and his book was a polemical work warning against Russian expansionism. It evidently struck a nerve in Victorian England. Mistrust of Russia became a deep and continuing theme in British foreign policy.

The map is entitled Sketch of the Acquisitions of Russia in Europe and Central Asia Since the Accession of Peter the Great. What we see on the map is the former heartland of Muscovy, left uncoloured, reaching roughly from Smolensk (about 200 miles west of Moscow) eastward as far as the Ural Mountains. Shown in colour to the north, west and south is region after region linked in a sweeping curve from Northern Finland to the Black Sea, then eastward through the Caucasus and Northern Persia and deep into Central Asia, then known as Turkestan, having its frontiers with Afghanistan and China. All these regions are annotated with the dates of their annexation by Russia, with a date range between 1720 and 1880. The word “acquisition” sounds like polite diplomatic language: these events certainly happened through military force, or the threat of it, but also by joint treaties with other powers. Poland and the Ukraine were also of great interest to Austria and Prussia, and were partitioned by the three powers acting together.

The territory involved was immense, and the table in the right-hand corner of the map drives the message home by showing that the Russian frontier had advanced 700 miles nearer to Berlin and Vienna, 500 miles nearer to Constantinople, 630 miles nearer to Stockholm, 1000 miles nearer to Tehran, and 1300 miles nearer to Peshawar. This last was perhaps the most alarming, for it threw up the possibility that Russia might even be casting its eyes on British India. Russia was now an empire, whose population had grown from fifteen million to fifty million in 160 years, and which shared a thousand-mile frontier with the British empire. This was the background to the “Great Game” between Britain and Russia, played out among diplomats and spies in the Himalayan region until the very end of the nineteenth century. The suspicion of Russia began to lessen only with the rise of German power, and the

Entente Cordiale by which Britain, France and Russia sought to restrain Germany. Russia’s military prestige was also severely damaged by its defeat in its war with Japan.

This eloquent map is a clear index to Anglo-Russian relations through the nineteenth century, and it conveys how Russia came to regard the Ukraine as its own territory, with Kiev placed on the Russian side of the frontier. It shows how long these historical enmities and ambitions may be in their making, and how long they can fester before they explode into the open.