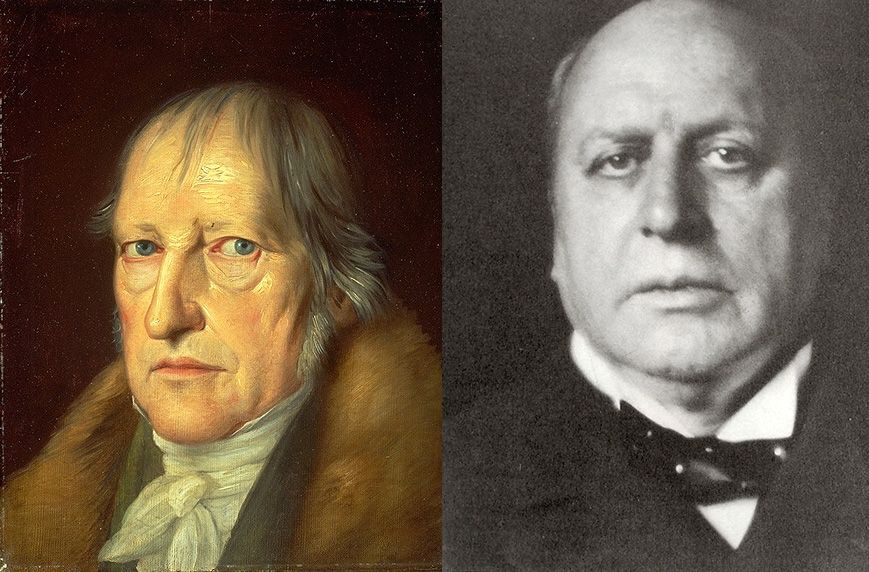

Behind the Masks – Hegel and Henry James

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Henry James: great names in philosophy and literature, the first from the very early years of the nineteenth century, the second from the very last years. Hegel was the deep and complex German philosopher who constructed a far-reaching and systematic analysis of God, nature, mankind and history. James was the author of almost twenty full-length novels and over fifty short stories, all depicting the lives of wealthy, fastidious personalities, those who constituted the social elite of English and American society from the 1870s to the end of the century. What possible connection could there be between these two very disparate characters, except for their eminence?

To begin with Hegel: he was once a titanic presence in the world of philosophy, and for a very good reason, namely that he claimed to have discovered the overarching force or principle which had shaped the physical world, the processes of nature and the civilisations of mankind. That principle he term Geist, which translates into English as either mind or spirit, a fortunate combination. In Hegel’s view, reality was not merely a collection of things that were stable, still less inert, but an immense process, or rather a system of interlocking processes which were following, a definable path of development, both singly and collectively. According to Hegel, these processes – physical, scientific, intellectual, social and historical – were all brought into focus in human consciousness; these spheres of activity were linked in an evolutionary process, a constant state of change and development, as was consciousness itself. This bold claim raised at once the overwhelming question: what was the driving-force behind this great process? Hegel considered it must be a mind or spirit, inherent in nature, and which came to consciousness in the human mind. He called this entity the World Soul, although he was not the first philosopher to use that phrase. Our world, our perceptions and experiences, form our consciousness, which mirrors back to us the consciousness of the World Soul itself. But the World Soul is not seen as something that exists “out there”, fully formed somewhere in the universe. Instead it develops and becomes real in the processes of the universe – in our case in human thought and history. This is what Hegel meant when he called his first great work, The Phenomenology of Mind or Spirit, where phenomenology means appearing, manifesting itself, becoming known. Thus the development of human consciousness takes place alongside that of some greater consciousness, which Hegel calls Absolute Consciousness. In Absolute Consciousness, the World Soul recognises itself, while human consciousness recognises its oneness with the World Soul.

It would be easy to conclude that Hegel was using the terms World Soul and Absolute Knowledge as rationalised equivalents of God, and to some extent this is true, for he never distanced himself entirely from Christian thought and Christian language. But he believed and argued that religion had expressed great truths through symbols and images, but that the time had now come for religion to turn to philosophy for a rational account of historical beliefs. History is vitally important in Hegel’s thought, and, uniquely among the classical pantheon of philosophers, he centred his system around history. He grasped that history is change and development, it is the phenomenology of human existence, and it is not random or purposeless, but is going somewhere. His finds his primary evidence for this in the human mind and human civilisation, which are moving from the lower to the higher, from the simpler to the more complex. He did not mean by this that history is a smooth constant advance towards perfection; on the contrary, it experiences repeated period of breakdown, irrationality and chaos, which require to be counterbalanced by the dialectical process which became one of the trademarks of Hegel’s historical theory. But in spite of these many crises, Hegel could write, “History is nothing else than the history of freedom.” This was central to his system: that mankind’s intellectual freedom and socio-political freedom are being driven, made apparent and real in history. Moreover this historical progress reveals that, “Spirit is the only reality,” because a trans-finite or absolute spiritual being is necessary to realise and sustain the finite spirit, that is, human consciousness. The culmination of this process lies, not surprisingly, in Hegel’s own philosophy: he saw himself as a great synthesiser, constructing bridges between the reality of history, the cultural achievements of humanity, the emerging power of science, and the religious instinct, which mankind had possessed from the beginning of time.

It will be clear that Hegel’s system is a highly intellectual construct: it is metaphysical, dealing with abstract, unverifiable concepts, and as such it can be criticised as verging on pure imagination. Yet this element of imagination is exactly what has kept Hegel’s name alive in philosophical debate, and it permits us to call his system visionary; it is powerful and inspiring in the way that art and music are, and like art its appreciation is largely dependent on “transcendental intuition”. Hegel had a profound interest in art in all its forms, seeing art as one of the most eloquent manifestations of spirit, both the human spirit and the world spirit which lies behind the human. He writes of culture and the art of literature in particular:

This has itself the most painful feeling and the truest insight about itself, the feeling that everything made secure crumbles to pieces, that every element of its existence is shattered to atoms, and every bone broken, moreover it consciously expresses this feeling in words, pronounces judgement and gives luminous utterance concerning all aspects of its condition.

And speaking of Christian religious art, he argues that imagery of Christ and other sacred subjects are taken deeply into consciousness, so that this art can become a form of sacrament, enabling to self to draw closer to Absolute Being. The spiritual authenticity of the best Christian art is contrasted with the fate of pagan, classical art, which is now purely aesthetic:

Trust in the eternal laws of the gods is silenced, just as the oracles are dumb. The statues set up are now corpses in stone whence the animating soul has flown, while the hymns of praise are words from which all belief is gone. The tables of the gods are bereft of spiritual food and drink, and from his games and festivals man no more receives the joyful sense of his unity with the divine being. The works of the muse lack the force and energy of the spirit which derived the certainty and assurance of itself just from the crushing ruin of gods and men. They are now for us beautiful fruit broken off the tree…It is not their living world that Fate preserves and gives us with those works of ancient art, not the spring and summer of that ethical life in which they bloomed and ripened, but the veiled remembrance alone of all that reality.

Christian art stimulated also the intellectual quest for God through thought and language; it engendered a profoundly serious theology, which paganism did not.

The work of art hence requires another element for its existence; God requires another way of going forth than this, in which, out of the depths of his creative night, he drops into the opposite, into externality. This higher element is that of Language – a way of existing which is directly self-conscious existence. When individual self-consciousness exists in that way, it is at the same time directly a form of universal contagion; complete isolation of independent self-existing selves is at once fluent continuity and universally communicated unity of the many selves; it is the soul existing as a soul. The god which takes language as its medium of embodiment is the work of art inherently spiritualised, endowed with a soul.

In striking passages like these we see Hegel, the abstract builder of arcane systems, as something else, namely a man looking deeply into history in order to discern what lies behind it. We can, he claims, look through the masks of history, culture, religion and science to disclose other dimensions of consciousness and reality. Effectively he was deconstructing the various realms of human experience, translating them into a new language. Perhaps we might even say that he was psychoanalysing the sweep of human history, seeking to identify the hidden instincts that moved it forward. In some ways Hegel can even be seen as a forerunner of Darwinism; not that the World Spirit should be identified as the controlling force behind natural selection; but it is evident that anyone who was familiar with Hegel’s ideas would recognise Darwin’s view of nature as embodying a vast process of continual change and development. It is beyond dispute that Hegel also had a profound and lasting influence on Marx who accepted the Hegelian vision of history as a process in which a real force was leading mankind to freedom. But Marx secularised that idea: to him that force was not a World Spirit, but economic logic and revolutionary social change. In terms of the history of western philosophy, Hegel offers the classic example of the school of Idealism, which can be defined in a number of ways, but perhaps the simplest is that there is a distinction between appearance and reality. Our ideas about the world are not formed merely by looking at things, but about the way our minds interpret what we see. Hegel’s work is an extended argument for that view, synthesising ideas from history, art, religion and science to demonstrate the way these things have all developed, and what in his view is the moving force behind that development, namely Spirit. To express this process, we may speak metaphorically of Hegel removing the masks of our world and our existence and penetrating to reality. Of course Hegel is very far from being the only thinker ever to pursue that goal; in fact it might be argued that a great part of the literature of mankind sets out to do that, in poetry, novels and drama, as well as philosophy, history and religious works; but Hegel’s contribution to that tradition is outstandingly rich, a richness that lies partly in his extraordinary and challenging language.

Hegel’s language is indeed immensely difficult, and there are times when the brain whirls when trying to follow him. He is a master of language, but a language that is partly secret, personal and mysterious, and with this he dares to take us into unknown regions. But he has a great lesson for us: that something transcendent must exist to sustain the immanent; that spirit is the only reality, and the self is Absolute Being. These principles sound more like religion than philosophy, indeed when measured beside Hegel’s vastly ambitious vision, it is today’s philosophy that appears remote, technical and dehumanised. I have said that Hegel devised his own philosophical language, but it goes beyond that, for it would be truer to say that he was a magician of language: if he wanted to make grandiose statements concerning God, Spirit, Idea, Reason, Mind, Consciousness, the Absolute, then he made them, and the result might be obscurity and torment for his readers; or alternatively it might be a re-education, a rebirth of imagination as an element within philosophy. He proclaimed his bridge between religion and philosophy when he wrote, “Without transcendental intuition it is not possible to philosophise.” His concentration on consciousness permeates his writing, for self-consciousness is the unity of being and thought. In the Incarnation for example, he argues, God becomes real, the Divine Being is given to the senses, he actually exists as he is in himself:

“God is attainable in pure speculative knowledge alone. That knowledge knows God to be thought, and knows this thought as actual being and as real existence. It is just this that revealed religion knows. The hopes and expectations of preceding ages pressed forward to, and were solely directed to, this revelation, the vision of what Absolute Being is, and the discovery of themselves therein. This joy, the joy of seeing itself in Absolute Being, becomes realised in self-consciousness, and seizes the whole world.”

The location of Absolute Being within the self-consciousness of the individual mind is strikingly reminiscent of the Hindu doctrine of Brahman-Atman, the world soul and the human soul, a theme that also became central to Emersonian Transcendentalism. We might sum this up by saying that God is present in the thought of God. This is the kind of mind-stretching statement which Hegel’s vision could produce, breaking through the masks of the physical everyday world, locked in physical space and time, to a spiritual reality. There is virtually no end to the power of Hegel’s speculative brilliance, even claiming as he did that if we trace the World Spirit back in history, we shall arrive at a point where we can, “understand God as he was in his eternal essence before the creation of nature and finite mind.” A philosopher who can make claims like that deserves to be heard, studied, wrestled with and honoured, now and into the future, perhaps indeed for as long as religions and philosophies endure.

To shift our attention from Hegel to Henry James is to feel like an astronaut re-entering the zone of gravity and setting foot once more on solid earth after days or weeks of a weightless life where there is no up or down. James’s works of fiction represent the culmination of the nineteenth-century psychological novel. His novels are inhabited by refined, wealthy, calculating figures, moving through elite society, involved with each other in a carefully ritualised ballet of manners. Overt drama is almost entirely absent; instead James takes us beneath the surface of their lives to reveal ambitions, secrets, conflicts, deceits and of course love, but usually of a troubled and certainly an undemonstrative kind. In the background, waiting to show its power, is always money, and the social position which it controls. The lives of these people unfold before us as if in an elegant, slow-moving film, and it is significant that the last fifty years have seen a stream of film and television adaptations of these novels, spreading the writer’s fame far beyond literary and academic circles. Today’s film-makers have been drawn again and again to the period costumes, the opulent houses and the splendid Italian surroundings in which the stories are set, while one of the great sources of their fascination is undeniably the element of deceit and its unmasking.

James’s role as the omniscient narrator is to take us inside the minds of two or three leading characters, whose feelings and experiences are analysed in enormous subtlety and detail. There is almost no actual drama, no violence, no storms of emotion, while events such as marriages, births and deaths take place off-stage. All significant action takes place in the mind, and is carefully conveyed to the mind of the reader in language that is fastidious and ultra-sensitive. Physical contact is rare, even between people supposedly in love, and rapid movement is virtually unknown; nobody runs, or falls or shouts in a Henry James novel. The author makes no attempt to arouse our emotions, rather he lures us slowly, step by step, into a pattern which he is weaving. In fact it is the gradual emergence of this pattern, rather than the excitement of the conventional novelistic plot, that is the author’s purpose. The central fact about these novels is that the author is constructing works of art, and his work has a close affinity with the work of the painter. Like the painter, especially perhaps the portraitist, his true interest is to penetrate beneath the surface of superficial reality. His great theme is deception and revelation, innocence and the pain of disenchantment. Over the years his novels grew longer as he held the story back, delayed the disclosure which must inevitably come, so that we may fully appreciate the destruction of the social masks. When this happens, unforeseen perspectives open before the characters in the novel, and also before the reader, as James makes us confront the essentially corrupt nature of the elegant society in which he moved and understood so well.

And this is where the great point of contact with Hegel comes strikingly into focus; but where Hegel sees beneath the surface of human existence to a noble, spiritual, transcendent force that is emerging in human history, James sees the individuals who fill his books as living a cold, blind, selfish and bitter life, not very far removed from a Dantesque place of punishment. It is the great lord and judge of that place, namely money, which is exposed as the deepest source of human misery. It is money that he identifies as permeating and perverting both the individual life and that of society, engendering egotism, selfishness, exploitation, deception and all the other labyrinths in which his characters trap each other. And the really striking resemblance to Hegel is James’s focus on evolving consciousness: for Hegel this evolution is a cosmic process, but for James it is a psychological drama which unfolds as the victims of this system become conscious of what is happening in their unhappy lives. James is not a philosopher but an artist using a uniquely crafted language to explore the hidden recesses of the human mind and experience, and this again is exactly what Hegel does, but on a completely different plane. Both these languages are complex, deep, subtle and demanding, precisely because they are attempting something new and difficult, each in his own unique way mapping the intricacies of consciousness. Here, for example, James carefully analyses the emotions of two elegant young women, Kate and Milly, at the end of a day spent exploring and enjoying Venice, when now they are relaxing and reflecting. Kate is a cool, self-possessed, articulate personality, while Milly is more reserved and enigmatic, and she is hiding the secret of a mysterious and undisclosed illness:

These puttings-off of the mask had finally quite become the form taken by their moments together, moments indeed not increasingly frequent and not prolonged, thanks to the consciousness of fatigue on Milly’s side whenever, as she herself expressed it, she got our of harness. They flourished their masks, the independent pair, as they might have flourished Spanish fans; they smiled and sighed on removing them; but the gestures, the smiles, the sighs, strangely enough, might have been suspected the greatest reality in the business. Strangely enough we say, for the volume of effusion in general would have been found by either on measurement to be scarce proportional to the paraphernalia of relief. It was when they called each other’s attention to their ceasing to pretend, it was then that what they were keeping back was most in the air. There was a difference no doubt, and mainly to Kate’s advantage; Milly didn’t quite see what her friend could keep back, was possessed of, in fine, that would be so subject to retention; whereas it was comparatively plain sailing for Kate that poor Milly had a treasure to hide. This was not the treasure of a shy, an abject affection – concealment on that head belonging to quite another phase of such states; it was much rather a principle of pride relatively bold and hard, a principle that played up like a fine steel spring at the lightest pressure of too near a footfall. Thus insuperably guarded was the truth about the girl’s own conception of her validity; thus was a wondering, pitying sister condemned wistfully to look at her from the far side of the moat she had dug from around her tower.

– The Wings of a Dove, Part Seven

The tone of this passage appears light, but James has planted certain clues to the relationship between these two: the “putting off of the masks” that they wear in public does not lead to mutual intimacy and understanding; instead what was unspoken, what they were concealing from each other, hangs in the air between them. We have already gathered that Milly may be dying; and gathered too that Kate is scheming to obtain at least a part of her great fortune. Milly does indeed die – her great wealth could not save her – but Kate’s plan comes to nothing, destroyed by its own inherent moral evil. Slowly and delicately James charts the personal cost of her deception, and shows how radically unfree human beings are, most of all when they are pursuing wealth and power by manipulating others. This is in obedience to the law that worldly success so often entails moral desolation.

There is no doubt that, within the richness of his prose, of his psychological analysis, and of his sensitive evocation of places, James placed a devastating critique of the social milieu of which he was such an expert observer. For the principle figures, every one of his major novels ends, to a greater or lesser extent, with failure, defeat, disillusionment and unhappiness. James himself was a profoundly enigmatic man, for in the very full record of his life there is scarcely any hint of the emotion which lies at the heart of so many novels, namely love. He cultivated many deep and satisfying friendships, but he neither married nor ever enjoyed a physical relationship with a woman, nor could he bring himself to describe such a relationship, except in oblique terms. He carefully guarded his celibacy, consciously steering himself away from any possible danger of compromising his freedom or his solitude; he stated explicitly in his fiction and elsewhere that the true artist must devote his life to his work, and avoid emotional self-surrender. He had no religion, but a distinct moral code of integrity and humanity, loyalty and compassion, which he opposed to the false values of the outside world. He devised, over time, a language that became ever more ornate and subtle, so that many readers have found it mannered, at times almost unreadable. He seemed driven to make his analysis of characters and motives ever more refined, because he wanted to lose nothing, not the slightest hint, of what was happening as his protagonists thought, planned, spoke and tried to steer their lives towards their desired ends. The major doubt, or question, about James’s unique and challenging novels, is whether the form, the edifice, which he creates is not too elaborate, too precious, too diffuse to do justice to his deep underlying themes? Is there not at times a wilful lack of clarity, a loss of contact with familiar reality, which alienates the reader? Where he avoids this danger, for example in The Portrait of a Lady, he writes an almost perfect work that is balanced, clear and accessible, and which carries a powerful message. In that work and in the more difficult ones, the great, the central motive behind his lifelong devotion to fiction was his passion to undeceive, to bring to light the reality behind the masks, and thus to make his novels an extended fiction capable of revealing truth. The world of Hegel and that of Henry James now seem infinitely remote to us; yet both have profound lessons for us, while they make us marvel at the magic of language when it is handled, mastered and transformed, by a great creative imagination.

Quotations from Hegel are all from The Phenomenology of Mind, translated by J.B.Baillie, 1910, reprinted 2001.